Max Lamb is an unassuming furniture maker based in the United Kingdom. His work is bold and uncomplicated, often locally made, and hangs in a balance between the radical and reassuring natures of design.

James Taylor-Foster: Tell me a little about yourself.

Max Lamb: I like to keep myself to myself, and I really do like it that way. I’m inwards rather than outwards looking, and I tend to just do my thing. I’m not confident that I can change the world – a lot of designers speak about the beauty of the profession, that they’re able to change the way people behave, the way they consume, the way that they eat. But I don’t think about it like that at all. I really enjoy making things.

You describe yourself as introspective, but I don’t necessarily see you moving from one siloed project to another – I’d say that you work in larger arcs. When you’re making something, are you thinking about a specific kind of user or are you simply lost in the material, in the process of making?

It’s a bit of both, but I would say—increasingly—the latter. I’m happiest when I’m lost in my own world and able to focus on the output, regardless of a user. That might sound selfish in as much as I’m not thinking about how I am serving a potential user but, for me, the protagonist is always the material. Second to the material is the method of manipulation. The ways in which I can transform a material, for instance, always involves me somehow – sometimes my hands, in contact with tools, sometimes my hands just pressing a button that allows something else to be the tool. I think that my most satisfying work, from a personal point of view, are those in which I’m making for the sake of making.

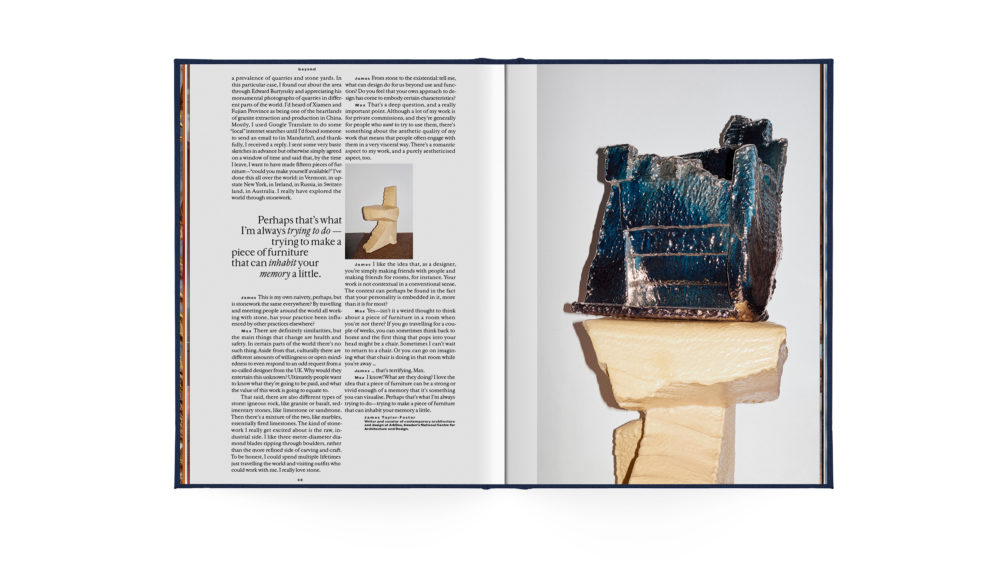

Let’s talk about expanded polystyrene for a moment, a material that’s very much within your toolbox, and recurs. There’s a liquidity to this material, a fluidity — almost as if it’s frozen in time. It certainly appears solid, visually and to the touch, but it gives me the sense that it wasn’t as solid at one point… and might not be again?

Yes! I’d agree. Polystyrene is, in many ways, very ephemeral. It’s an almost worthless material, or at least that’s the preconcenception we have. It’s often just seen as the stuff inside the packaging that you normally throw aside as you’re trying to find the thing that you’ve longed for for so long. The beauty of this is that I can also treat it in a similar way – as in, I don’t have to be too precious about it. I can work with it with speed and spontaneity, and this speed is embodied by the final pieces. The shapes and the textures are weird; sometimes they’re ‘wrong’. And once all these bits of carved and hewn pieces of polystyrene are assembled and composed into furniture, they remain fragile. I often can’t test them out for comfort – it’s only once I’ve coated them in polyurethane rubber and constructed an exoskeleton that I know whether or not I’ve succeeded, and then it’s too late. I choose to work with this particular type of coating because it’s incredibly quick. It’s chemistry happening before your eyes, flowing from this huge industrial spray gun: this liquid is pumped and coats surfaces very thickly, really quickly, and then drips. And as it drips, it suddenly freezes – it dries in three seconds.

Three seconds?!

Yes! From the moment it comes out of the nozzle and hitting a surface, it’s just three seconds. I use it incorrectly, of course – professionals tell you not to stand close to the work, and I keep my finger on the trigger rather than pulsing it as they advise. They tell you to keep the gun moving to not get build-up, but I like the build-up because if you add it thickly enough and with enough speed there’s a high enough volume of material for it to drip.

When I first started making furniture using this material, the company wouldn’t let me spray. So I’d stand there, in agony, as I watched them spray my work. Every two minutes I’d have to enter the spray booth to ask them to put a bit more on, and it was a couple of years before they finally let me have a go myself. I must have been such a difficult customer, but this has been vital for me to get the most out of the material. I need to do this because I’m not very good at designing on paper. I’m only really any good when it comes to actually making something.

What’s your stance on mass production, or the production of many of one “thing”?

If I go back to 2006, which was the year I graduated from the RCA (Royal College of Art), my degree show was called Exercises in Seating. I then reused this title in 2015 when I did something similar for Salone in Milan, presenting forty one chairs and stools and benches produced over the nine years since I’d graduated. But this project really began in 2005 when I was at the beginning of my second year at college and was really trying to understand who I was, or could be, as a designer. I couldn’t afford a studio at the time, but going back to school gave me access to all sorts of machinery. I realised then that I always need to keep my hand involved in design as much as possible, but I also realised that I’m quite good at experimenting with things.

It’s very difficult as a young designer to say: “I’m going to make ten thousand of something,” unless you’re invited to work on a design at scale for a company. At the time I would have longed for that sort of opportunity, but that just didn’t happen. And yet it was important that I could show my hand, so to speak. The point of Exercises in Seating more generally was to select one typology—the seat—and explore as many variables as possible within that world. I could upscale one into a batch of ten or twenty, and so on, and this was really my way of dabbling with production en masse while trying to show my ability, too. After that, my work took on a very hands-on approach and that’s what I’ve carried on doing, informed by the fact that I spent a lot of time exploring the idea of value – monetary value, sentimental value, and so on. I was very critical of design for homogeneity and global consumption at the time.

Do you still hold that view?

I do, but I also understand that there’s economic diversity across the world. I find it ironic that we’re designing things for consumption in Europe, for instance, and yet it’s being produced on the other side of the world, wherever that might be. This is such an interesting moment to be in right now – in the midst of a global pandemic. The world is locking down and the typical supply streams that we’ve been so dependent on, with a very false sense of ease in just-in-time principles, for example, is becoming clear. I’ve been scrambling to keep my own momentum and, although I’m generally quite considerate about where I’m sourcing materials from, right now I have little choice but to find things as locally as possible. I’m using every scrap of material that I’ve been accumulating inside and outside of my workshop for the last six years just to maintain a little bit of progress.

Do you largely make things on-site?

I do. For example: Ilse Crawford was designing a project in Hong Kong, and they wanted me to make the concierge desk and some of the lobby furniture, so I went there and made it all in the south of China. It made more sense for me to hop on a plane and go there to make fifteen pieces of furniture using seven tonnes of granite.

So, talk me through it. You arrive in China — what happens then? Do you source materials before you arrive? How do you find a workshop? I suppose what I’m essentially asking is: do you bring your practice to China, or do you find your practice bleeding into what goes on there?

I try not to export too much other than myself and my open mindedness. I like to just turn up and try to be resourceful and spontaneous. The purpose of these trips is to produce something, and usually that something is very specific. It needs to fit within an existing space, for instance. I’ll do as little as I can before I get there while also being confident that it’s not going to be a wasted trip. I need to have a few things in place, and so I do some initial research to firstly identify a place where I know there’s a prevalence of quarries and stone yards. In this particular case, I found out about the area through Edward Burtynsky and appreciating his monumental photographs of quarries in different parts of the world. I’d heard of Xiamen and Fujian Province as being one of the heartlands of granite extraction and production in China, but mostly I’d used a bit of Google Translate to do some “local” Internet searches until I’d found someone to send an email to (in Mandarin!) and, thankfully, received a reply. I sent some very basic sketches in advance but otherwise simply agreed on a window of time and said that, by the time I leave, I want to have made fifteen pieces of furniture — “could you make yourself available?” I’ve done this all over the world: in Vermont, in upstate New York, in Ireland, in Russia, in Switzerland, in Australia — I really have explored the world through stonework.

This is my own naivety, perhaps, but is stonework practice the same everywhere? By travelling and meeting people around the world all working with stone, has your practice been influenced by other practices elsewhere?

There are definitely similarities, but the main things that change are health and safety. In certain parts of the world there’s no such thing. Aside from that, culturally there are different amounts of willingness or open mindedness to even respond to an odd request from a so-called designer from the UK. Why would they entertain this unknown? Ultimately people want to know what they’re going to be paid, and what the value of this work is going to equate to.

That said, there are also different types of stone: igneous rock, like granite or basalt, sedimentary stones, like limestone or sandstone. Then there’s a mixture of the two, like marbles, essentially fired limestones. The kind of stonework I really get excited about is the raw, industrial side. I like three metre-diameter diamond blades ripping through boulders, rather than the more refined side of carving and craft. To be honest, I could spend multiple lifetimes just travelling the world and visiting outfits who could work with me. I really love stone.

From stone to the existential: tell me, what can design do for us beyond use and function? Do you feel that your own approach to design has come to embody certain characteristics?

That’s a deep question, and a really important point. Although a lot of my work is for private commissions, and they’re generally for people who want to try to use them, there’s something about the aesthetic quality of my work that means that people often engage with them in a very visceral way. There’s a romantic aspect to my work, and a purely aestheticised aspect, too.

I like the idea that, as a designer, you’re simply making friends with people and making friends for rooms, or parks. Your work is not contextual in a conventional sense. The context can perhaps be found in the fact that your personality is embedded in it, more than it is for most?

Yes – isn’t it a weird thought to think about a piece of furniture in a room when you’re not there? If you go travelling for a couple of weeks, you can sometimes think back to home and the first thing that pops into your head might be a chair. Sometimes I can’t wait to return to a chair. Or you can go on imagining what that chair is doing in that room while you’re away…

…that’s terrifying, Max.

I know! What are they doing? I love the idea that a piece of furniture can actually be a strong enough or vivid enough of a memory or an image in your head that it’s something you can visualise. Perhaps that’s what I’m always trying to do – trying to make a piece of furniture that can inhabit your memory a little.