When the American literary critic Richard Ellmann submitted a request to James Joyce for an outline of Ulysses to assist in biographical research,1 the author reputedly scoffed: “If I gave it all up immediately, I’d lose my immortality!” He tempered this response with a challenge: “I’ve put in so many enigmas and puzzles that it will keep the professors busy for centuries arguing over what I meant.”2 Comprising three books and eighteen episodic narratives, Ulysses is often read as a tale tangled in its own indecipherability, feeling peculiarly outside of any time or place and yet absolutely in and of Dublin. Through testimonies and storytelling, Joyce deploys its three protagonists—Stephen Dedalus, Leopold Bloom, and Molly Bloom—as vehicles to moot the duplicitous fallibility of a single frame of reference. When voices chronicle in concert, the result can be deceptive: if three’s a crowd, one’s deceit.

In his epilogue, uttered on his deathbed somewhere in Zurich, Joyce is said to have inquired: “Does nobody understand?” I, for one, do not understand Ulysses. I sometimes wonder if I ever will. I do persist, however, and a recent leaf through Hades (Ep. 6) recalled the memory of an exhibition. It too had three protagonists: the sculptor and photographer Thomas Demand; the writer, philosopher and filmmaker Alexander Kluge; and the stage and costume designer Anna Viebrock – and they too spoke in concert. It was called “The Boat Is Leaking. The Captain Lied.”

This is a review in its most literal sense: a squint into the rear-view mirror toward a cultural work that we can no longer experience. It stands as a delayed response—tinted rose, perhaps—to the context around twenty-one attempts and transformations by Demand, Kluge, Viebrock and its curator, Udo Kittelmann. These four image-makers, used in its broadest sense, reacted to and with one another to establish a shared impression of the world. This impression was then consolidated in order to expire. As such, this is not intended as an appraisal of the montage itself, nor is it a commentary. It is a digestion of what was largely unseen, backgrounded, and of that which lodged itself in the mind’s eye: the collaged environment that circumscribed a unique collaborative project – since extinct, still extant, and, like my reading of Ulysses, entirely enigmatic.

In an interview with Giovanna Manzotti, published just after the exhibition opened, Kittelmann described the show as a panorama in excerpts and scenes that describe a world caught up between storms and calm, threats and hopes, standstill and transitions, and truths and falsehoods. “Don’t expect a white cube,” he declared. “It will be the very reverse. Objectivity won’t make it possible to keep control.”3 One can imagine the conversation that Kittelmann, Demand, Kluge, and Viebrock had in the summer of 2016. It was, lest we forget, the moment in which voters of the United Kingdom chose by a hair’s breadth to turn a’starboard and sail headlong into the turbulence of repudiation, uncertainty, and self-denial. (Hindsight, of course, is a wonderful thing.) By that point, preparations for “The Boat Is Leaking…” were well underway. Against a backdrop of fragmentation and disenchantment, it was a spirit of aspirational unity that threaded the dialogue between the three artists and their curator. Without knowing what the project might involve to create, look like, or how it might be experienced, it was a postcard of the Italian painter Angelo Morbelli’s 1883 Giorni… ultimi! [“Last Days”],4 mailed around the group by Demand, that set their course.

In the picture a uniform gaggle of tired, elderly men, greying and dressed in black, are sat on wooden pews in a tall, tired waiting room. But waiting for what? The answer, in all its existential morbidity, is death. The men depicted in Giorni… ultimi! are retirees at the Baggina (known formally as the Pio Albergo Trivulzio), one of Milan’s oldest continuously operating retirement homes for the destitute and dying. They are reading, sleeping, praying, writing, glancing over their shoulders. Brow mopping and heads in hands they appear untroubled and resigned. The group’s initial reading of the picture on the postcard was a misunderstanding. Having not researched the work and simply reading into its surface, they came to the conclusion that the men depicted were retired sailors eking out their final days in a hostel – a false image, or an “error in navigation” to use Kittelmann’s words, which subsequently weighed anchor and gave rise to the maritime metaphors that was to guide the narration of the show. Misunderstanding or otherwise, it became a mutually received action statement. For Kittelmann, the “picture renders tangible the truth that humanity is not a mere collection of individuals.” (This is, he argues, one of the reasons why we today find ourselves precarious.) It set an initial direction for a joint project early on, helping the group to find a common direction.5

The stage, therefore, was set – conceptually, but also spatially. The Fondazione Prada—a private cultural establishment conceived of and steered by the Milanese fashion mogul Miuccia Prada and her husband Patrizio Bertelli, who share a collective fortune of around $2.7 billion—had offered their 18th Century Venetian palazzo, Ca’ Corner della Regina, for the show. Unlike its Milanese counterparts—a sprawling complex of spaces in Largo Isarco designed by the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, alongside the Osservatorio, tucked into the triforium of the Galleria Vittorio Emanuele II—the foundation’s Venetian outpost, moored to the northern fringe of San Polo, is a historic monument of significance. The Fondazione Prada is merely its custodian, inhabiting rather than occupying it’s painted halls and courtyards which, by virtue of their splendour, have been seamlessly emulsified into the Grand Canal’s thickened lining of façades.

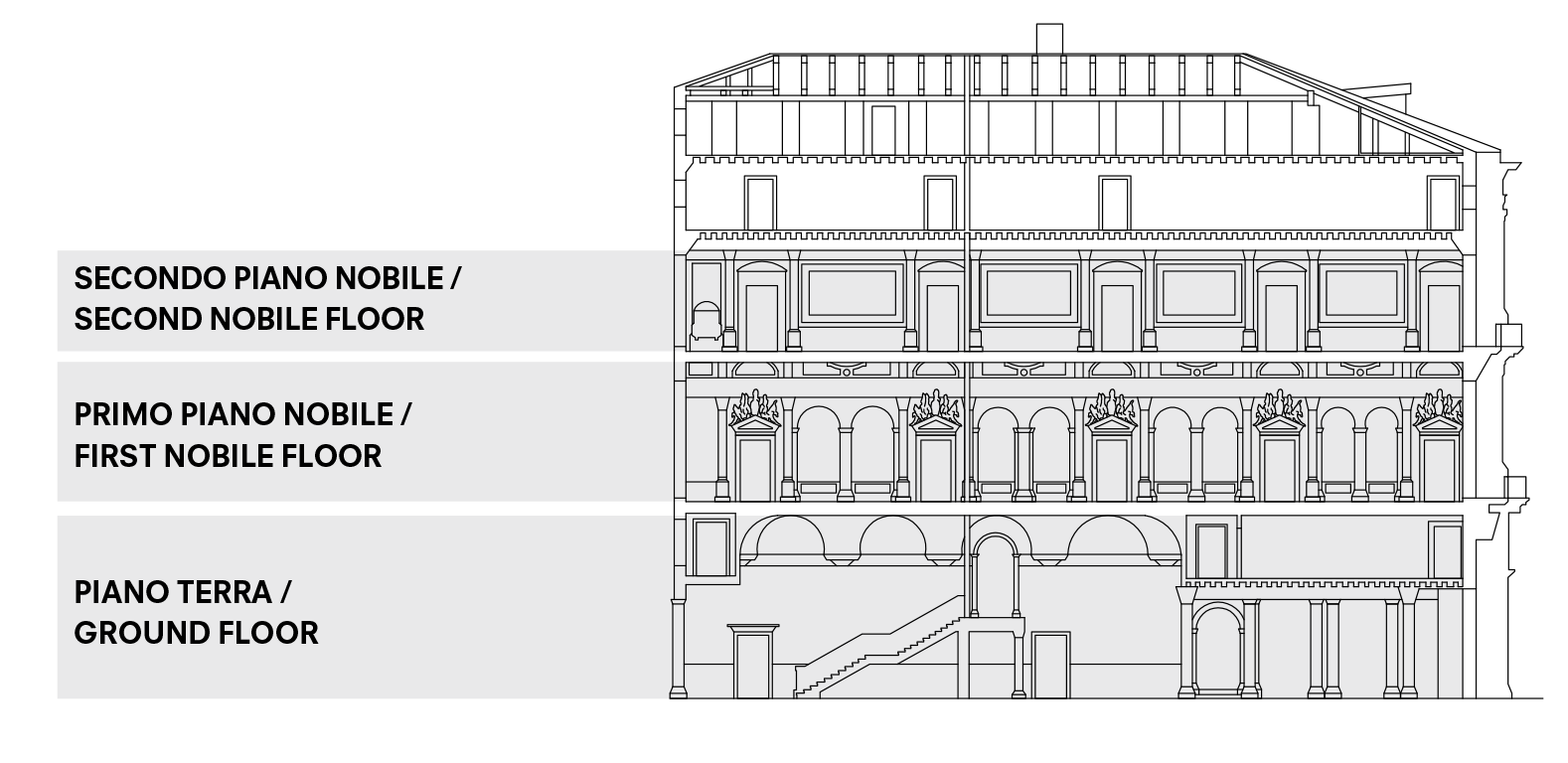

The palazzo—charged by history, as so much in the city is—presents a challenging sequence of spaces for any artist or curator to conceptualise, yet alone realise, an exhibition. Obtained by the foundation in 2011, the rooms are grand and uneven, teeming with sculpted mouldings and frescoed to the hilt. In 1454 it saw the birth of one Caterina Cornaro. Noble by filiation, her family—known as the “Corners” in local dialect—boasted among its ancestral holdings a salutary smattering of Patricians, Cardinals, Doge and Dogaressa. Caterina, however, was destined to outrank them all: she was to become the last ruling Queen of Cyprus and, upon the untimely death of her husband at only thirty-five, was avidly designated a Daughter of St. Mark by the Venetian Republic so that they might enfold the island into the burgeoning Empire ostensibly in her name.6 Back in Venice, the original Byzantine-Gothic palazzo that the family had assembled during their ascent soon fell into disrepair. (Caterina was the last of her line, bequeathing Ca’ Corner to Pius VII.) The palazzo, later rebuilt in a classical style, and not dissimilar to that of Baldassare Longhena’s Ca’ Pesaro, would later house the Biennale di Venezia’s archive of contemporary art.

Dwelling in the palazzo’s rooms, corridors, and staircases, “The Boat Is Leaking…” sought to supplant the layered history that it was to become a part of. Among the objects of film, art and theatre media, there was a sense of the unfolding dialogue that had led to their seamless, or consciously fractious, interactions. The inhabited spaces—which might more accurately be described as scenographies, or works of theatre—were tethered to one another with deft sleight of hand. The arrangement of the works within the rooms, their proximity, and the interplay between built “sets” and the inner-lining of the palazzo-proper amplified a sense of unease, progressive and difficult to discern. These scenographic interventions oscillated between the background and the fore, demanding your attention for a moment before appearing to dissolve entirely. This yawning, see-sawing performance of total curatorial control and spatial spontaneity was at once disarming and, at best, disorienting.

Nothing was as it seemed – a conceptual consequence, I’d surmise, sparked by the role that Giorni… ultimi! played at conception. This picture, mangled by misunderstanding and interpretation, had a direct presence in the show. In a section of the primo piano nobile—Ca’ Corner has two—Viebrock constructed a large fragment of the room depicted in the painting was reproduced at a scale it might have been, if not truncated. The very same two-tone beige wall, the same wooden pews, and two solitary lights suspended from the frescoed ceiling. The original Giorni… ultimi!, alongside other works by Morbelli, were hanging in an adjacent room also treated by Viebrock and featuring a parquet floor with an artificial ceiling of translucent glass, blanketing the room with white light.

Spatial interventions of these sorts infiltrated the palazzo throughout at times complementing, and thereby unifying and, at others, undermining entirely. On the ground floor of the palazzo—a large, brick-lined space with three staircases which ascend to the piano nobile, once the place in which goods and chattels from far-flung outposts of the Venetian Empire were stored for sale—stood Kluge’s Die sanfte Schminke des Lichts (The Soft Makeup of Lighting, 2007). All windows to the water had been covered by thick, black curtains and this, a sublime, intimate study of the human face and the effects of light, from stage to candle, played on loop. To the left and right stood two installations by Viebrock—Hotel door and Safari bar door—each embedded in an existing portal and ante-room, illuminating the space between with blue and red neon light.

“Our complete existence could in fact be compared to a building and its diverse functional spaces,” Kittelmann argues. “Such a building is also a vessel, a body, whereby the individual rooms of the building can be read as the necessary organs of a biological body, i.e. the brain, heart lungs, etc., but also as the germ cells of drives and phantasms.”

In every likelihood, this attempt is as enigmatic as the work it has tried to allude to. Acceptance of indecipherability—of complexity, incoherence, and misapprehension—is, perhaps, something to strive for. “Everybody knows the boat is leaking/Everybody knows the captain lied”.7 That’s how it goes.

The Boat Is Leaking. The Captain Lied. was at the Fondazione Prada in Venice, Italy, between May and November 2017. A three-volume book edited by Udo Kittelmann, including the English and Italian editions of The Great Hour of Kong. A Chronicle of Connections by Alexander Kluge, accompanied the show.

Read at source.