One of the first WhatsApp messages I sent Virgil Abloh was a quotation from Marcel Duchamp in which the artist mused on how he felt

as if everything that had gone before […] had been created by serious people who considered life a serious business and that it was necessary to produce serious things so that serious posterity would understand everything that these people, serious for their epoch, had done. I wanted to get rid of that.

A fortnight later I found myself in Paris’s Palais-Royal, sitting on a rainbow runway assembled for the unveiling of Louis Vuitton’s spring summer 2019 men’s collection—Abloh’s first as artistic director of the line. Unable to untwine what I had experienced that afternoon—a celebration of the dissonance between an object of design and the interpretation of that object of design—from Duchamp’s words, I continued to dialogue with Abloh. “It’s basically my graffiti on the wall,” he acknowledged, “so I’m glad I haven’t read that quotation before. I always get super apprehensive when I hear something that strikes so true.”

Abloh is open about the influences that those who have come before him—including Duchamp and his readymades—have played in shaping his evolution from a student of architecture at the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) in the early 2000s to contemporary multi-hyphenate whose activities include, but are by no means limited to, DJ (Flat White), wordsmith, scenographer, graphic artist, artistic director, fashion designer, and, as an agglomerate of them all, celebrity. Generous, assertive and self-assured, he has an uncommon ability to identify his precise position in the expanse of global cultural production, coupled with an uncanny talent for finding ways—methods, tools, partnerships, etc.—to tip the scales of the industries he’s immersed in away from the normative and toward his perception of originality in our time. Obsessed, in equal measure, by the established and the yet-to-be, he is driven by an effusive and potentially contagious curiosity. This is about the balance between what he often refers to as “the purist” and “the tourist”:

The purist is the one who crosses their legs and looks at a work of art with their fingers on their chin and then gives you a million reasons as to why this thing they’re looking at is important. The tourist, on the other hand, is somebody who is equally as interested in that work of art but simply looks on it as an object. In that space between is an emotional response, and this is the common denominator. What’s frankly wrong with the ‘art world’ and the ‘fashion world’ is that when you use these terms it has the effect of alienating people. This is what I’m trying to dismantle.

As audacious and direct as Abloh’s rhetoric can seem, it is not hyperbole. As both a persona and a trademark, the two now seamlessly spliced together, Abloh is a whirlwind of activity. Aside from his Louis Vuitton collection he has, in 2018 alone, dropped two new lines for his own fashion label OFF-WHITE c/o VIRGIL ABLOH™ (which he started in 2013, one year after discontinuing his first label Pyrex Vision), opened a number of new retail spaces in Asia and Europe, unveiled a constellation of objects with IKEA in Älmhult, Sweden, opened an exhibition in collaboration with fashion platform SSENSE in Montreal, presented the Nike x OFF-WHITE “QUEEN” collection of sneakers and sportswear for Serena Williams, staged the first “TELEVISED RADIO” for Beats 1 on Apple Music, unveiled the artistic collaboration “TECHNICOLOR 2” with Takashi Murakami at Gagosian in Paris, and stood at the decks of more festivals than any one person could ever attend. Parsing through these projects as individual episodes would be futile — it’s not the intention behind this body of work. Often overlapping anomalously, they represent intentional acts of design that ricochet off one other; cumulatively they amount to a narrative writ large across social media, web-shops, and retail outlets, and devoured by followers and consumers in real time.

Storytelling is always a delicate game of seduction; the power of any narrative rests on its author’s ability to articulate his or her own thoughts, but the key is knowing how, what, and when to divulge and disclose in the bridging of ideas from one cloistered mind to another. Abloh’s public and professional life is staged as a work of art, and its value is generated by conflating a certain artistic merit with the marketable power of his Midas brand mark (his trademark-cum-autograph often takes the form of block capitals, bracketed by straight quotation marks, inked on the soles of sneakers). In the case of “CUTTING ROOM FLOOR” Virgil Abloh™ c/o SSENSE — his aforementioned exhibition at SSENSE’s David Chipperfield-designed retail space in Montreal — the project was billed as “a never-before-seen view into the artist’s inner workings”. A partial recreation of Abloh’s home studio, the installation came complete with stud walls and laminate wood flooring, and featured an amalgam of objets trouvés pooled with personal effects. By SSENSE’s own description, it was also positioned as a conduit to further “the myth of Virgil Abloh” and launch in parallel a new collaborative line called Virgil Abloh c/o SSENSE. Among pens, sketches, and models were a number of books and architecture periodicals repackaged as limited-edition objects for sale, i.e. signed by Abloh and sealed in plastic by SSENSE. Monographic issues on Vann Molyvann, Jean Nouvel, Peter Zumthor, and Herzog & de Meuron sat next to a copy of Rem Koolhaas & Hans-Ulrich Obrist: The Conversation Series, Volume 4, this apparent 00s starchitect fandom presumably being a carry-over from Abloh’s student days. Where storytelling is concerned, “CUTTING ROOM FLOOR” constitutes a simple blend of fact and fiction — the construction of a myth before our very eyes.

In some cases, the formation of this narrative has been in process for longer than it might at first seem. On June 9, 2018, @virgilabloh posted on Instagram a photograph of a new suitcase produced in collaboration with the renowned German luggage manufacturer RIMOWA. Its form is as archetypal and recognizable as any other on the company’s roster; it functions in the same way, too — i.e., you can put things in it and roll it through the airport. The crucial difference is that it’s made almost entirely out of transparent polycarbonate. Everything you pack inside is visible to everyone, from ground handlers to customs officials. Sold out everywhere and almost impossible to find less than two months after the initial drop, the suitcase had in fact been designed four years prior. “It couldn’t have come out [earlier] because it wouldn’t have had any context,” Abloh explained. “It wouldn’t have gotten a response. I had to ask myself when the right time would be to present the idea of a non-branded suitcase that was all-clear, and that this non-branded, all-clear suitcase would look as though I had designed it.” He likens his sense of intuition to throwing a dart into the wind: “If you know which way the wind is blowing then you can work out exactly which direction to aim at the dartboard,” he argues. “It’s about intercepting ideas in the culture.”

The extent to which this level of free-form thinking leads to real-world production is possible because Abloh is a persistent master in the tricky art of collaboration. Indeed collaboration is the thread that weaves through all of the above. Be it with IKEA—the predominant space invader of our time—Nike, Louis Vuitton, RIMOWA, SSENSE, or under the OFF-WHITE umbrella (where he’s done collaborations with over a dozen different brands), each project of whatever scale or potential impact belies a tight chain of alliances. This mesh-network simply requires that Abloh point his attention to the right project at the right moment. “Only things I care about rise to the surface. I’ve managed my time just based on whatever I care about, and this is perhaps the biggest rationale behind my practice. It’s all one body of work — new ideas stem from another idea all of the time.” This, at least, is one side of the coin. The other, Abloh explains, centers on understanding the context of an action: an observation that gave rise to his “three percent approach,” a dictum propounding that three percent—not one, not ten—is the necessary figurative amount of addition or amendment required to recast an object from one thing into another, and, in so doing, claim and commercialize it as something fresh. This approach can be seen at work in the sneakers developed for Abloh’s OFF-WHITE x Nike collaboration, one of the U.S. label’s first major non-athlete collaborations (not counting Nike’s aborted Yeezy venture). Rather than waste time attempting to reinvent the sneaker from first principles, Abloh took, for example, an existing Nike Air Presto, attached a zip tie to its laces and printed “ “SHOELACES” ” in block-capital Helvetica characters on the shoelaces and “ “AIR” ” on the heel, thereby elevating the footwear, through a “contextualizing” gesture, into an article of rampant consumerist lust. “I like to think of design nowadays as a thinking person’s game,” he explains. It was at IIT that the penny dropped. “I saw a ceiling that I was getting stuck under” — the idea of the architect with a capital “A” or designer with a capital “D.” “I was very much sipping the Kool-Aid, believing that I needed some sort of radical aesthetic, and that I needed to come up with some vocabulary for this radical aesthetic to make it valid. I realized then that all I needed was three percent; that three percent left hanging in a room or on a T-shirt could let you know that I was there. I could spray a line, or I could reclaim the whole thing, but as long as I contextualized it, it would make sense.”

What’s largely misunderstood, Abloh believes, is that it’s the capacity to edit, refine, and package that actually allows people to ascend. Once he had figured this out he could perceive at which point he was positioned on the timeline of history: who he connected with from previous generations—mentors, in other words—and who from younger generations he could connect with and give buoyancy to today. “When I was searching for my signature, trying to understand what my DNA could be, I asked myself, ‘If I draw a regular black line 30 times, what makes one of those lines different? What makes that line mine?’” This is at its core an editorial strategy: Abloh is the ultimate editor in brief. “I liken everything that has come before our moment to the rule of law; I’m just trying to literally edit the law by placing the work I’m doing now into context.”

Context—dependent on but separate from content, which today tends to describe any product of a creative action—is one of the argots of our time. In the very first issue of Wired magazine, its founding editor Louis Rossetto declared that, in “the age of information overload, THE ULTIMATE LUXURY IS MEANING AND CONTEXT [sic].” The year was 1993. (In the interest of context, Abloh was 13 years old at the time; I was two months.) A quarter of a century later, Rossetto’s remark is more resonant than ever. The collective awareness developing among those who engage with the Internet and, by extension, the information age, is that it is less of a horizontal “web” and more comparable to a coiled spring. Since 1993 there have been more Rossettos. The former theoretical physicist Michael H. Goldhaber, who concretized the concept of the “attention economy” in a 1997 issue of Wired, has assumed an almost prophetic aura to those trying to sidestep the inescapable maelstrom of self-entanglement and opportunity that cyberspace proffers. Rob Horning, who stands among the most perceptive observers of this condition, posited in a recent issue of Even that as cyberspace and reality seep into one another’s domains, “getting attention is more significant than paying attention.” The summer 2018 issue of Berlin-based magazine 032c was titled THE BIG FLAT NOW: How to Be Everywhere, Anytime, and Everyone at Once and billed as a field guide for negotiating contemporary culture.

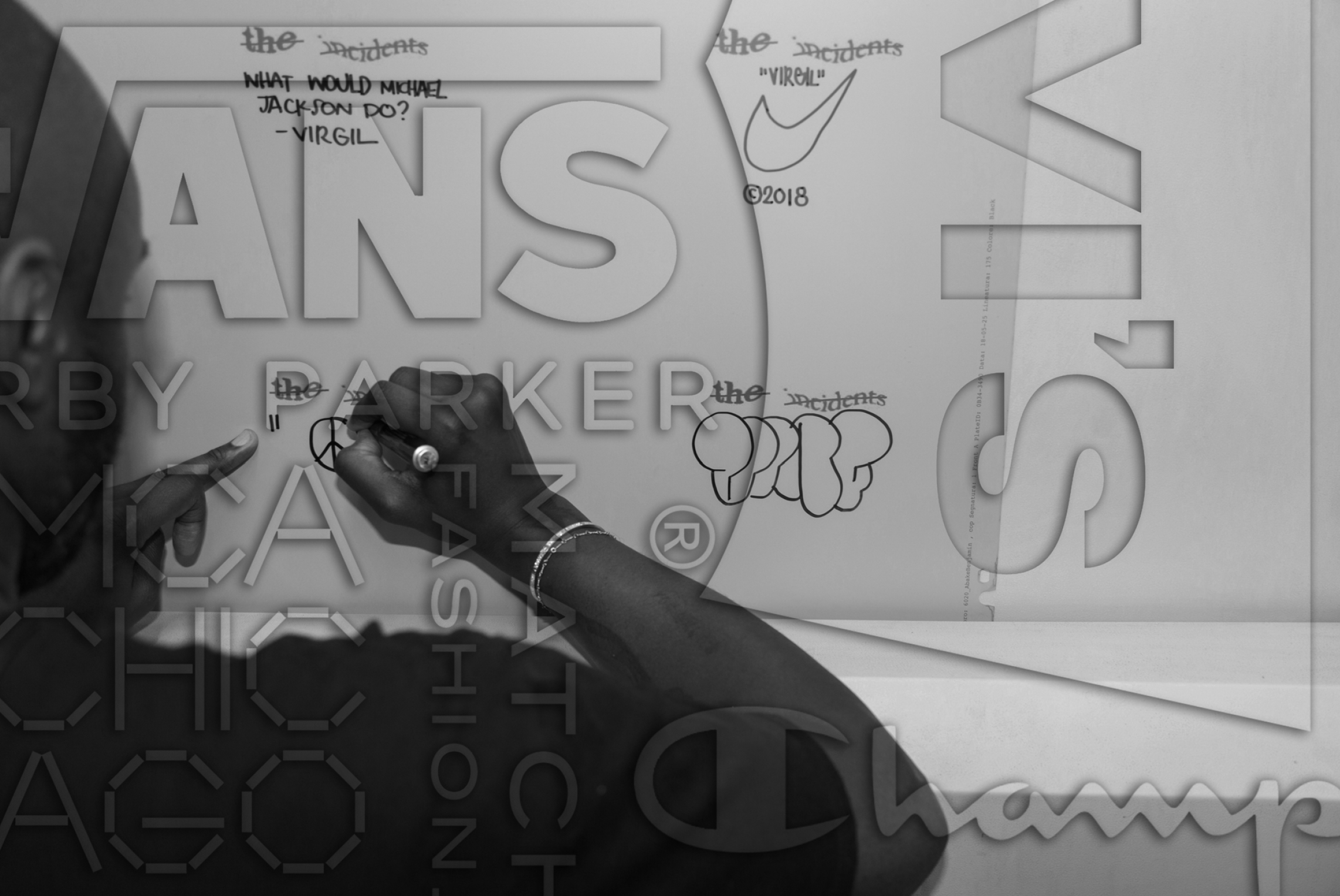

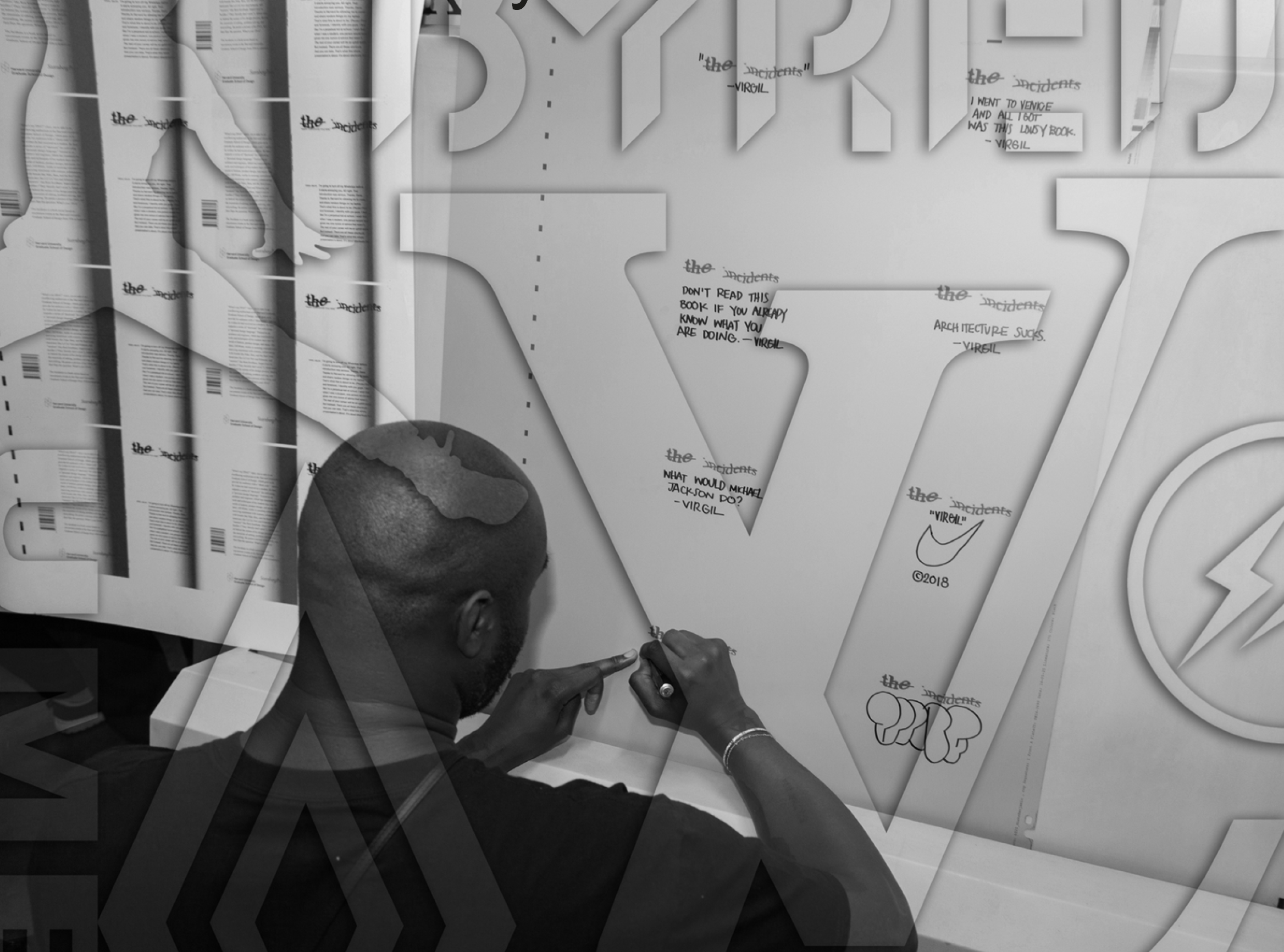

Whether or not Abloh is a product of this sort of insight, a beacon for its syndication, or one of its prime movers remains an open question. My first encounter with him was an edited one — de- or re-contextualized not by way of Instagram’s algorithm but through a book published by the Harvard Graduate School of Design (Harvard GSD) as part of the school’s Incidents series. It consisted in an edited transcript of a lecture Abloh gave at Harvard GSD on October 26, 2017 entitled ““INSERT COMPLICATED TITLE HERE“.” On the day itself, the audience appeared, by Abloh’s idiom, braced in “italic posture”— sitting with bated breath and ready to receive his gospel. The context in which this lecture and, by extension, the book occurred was, according to Jennifer Sigler, Harvard GSD Publications’ editor in chief, “outrageous.” “It was a true incident,” she recalls; “It was not a formal part of the GSD program and wasn’t planned.” Abloh had been invited to Cambridge by the architect Oana Stănescu, a faculty member and co-founder of the now-defunct Family New York studio, which had previously worked with OFF-WHITE on a number of their retail stores and also with DONDA, Kanye West’s creative-content company (of which Abloh was formerly the artistic director). After Abloh had tweeted the date and time of the lecture, Harvard’s communication department was flooded with emails and phone calls, and on the day, attendance greatly exceeded the auditorium’s capacity of 500. If the talk was “the ultimate event,” it was also the ultimate incident. Among Sigler’s favorite Abloh one liners that evening was a characteristic example of motivational modesty: “Failure is as real as Halloween ghosts.” “There’s something liberating in his attitude,” says Sigler. Yet it is the attitude, or the aura of an event, that poses a challenge to the editor of a publication seeking to harness the spectacle of that now-past event. For Sigler, the “book is not about canonizing Abloh but about capturing his ideas and work at a particular time and place.” It’s also about treading a notoriously fine and flimsy line: how, as an editor, can you imbue a translation of the spoken word with the clarity that the printed page demands while maintaining its tone and spontaneity? Abloh’s command of language is undoubtedly captivating—his “timing and restraint,” in the words of Sigler—and, after processing by deft editorial hands, it has been successfully captured in the book’s pages. (Needless to say, the book launch, organized by Harvard GSD in Venice, Italy, in May 2018 at a local printmaker’s during the Architecture Biennale, drew an equally large and enthusiastic audience, thanks to Abloh’s attendance. Images from the event, taken right before the space had to be shut down due to overcrowding, illustrate these pages.)

Speaking at Harvard was a significant moment in Abloh’s meteoric upward arc, not only for its message but also because—through a single tweet—he was capable of reshaping a simple lecture into a major event. Through the will of those he momentarily collaborated with, coupled with the engagement of a wider audience they didn’t realize they had access to, the event transpired. “I’m trying to time-capsule the feeling that I’m an outsider,” Abloh has said. Years ago, and perhaps still to this day, he would reflect on the fact that he didn’t see many people that looked like him. He didn’t come from that place. He didn’t have the entitlement that said, “I’m supposed to be here.” “I’m now looking to cap this off and move onto the next chapter of work. But that’s just my disposition, you know. That’s where my ideas come from. You and I have spoken a lot about editing, but what actually happens first is how something becomes remembered.” While it’s significant that an acclaimed African-American art director and son of Ghanaian immigrants can draw a broad audience to a lecture at Harvard, it seems even more significant that an African-American—after having successfully taken streetwear to new audiences—is now leading one of the world’s most revered luxury fashion houses. At the Harvard lecture and the launch of his new collection in Paris, both “tourists” and “purists” were, literally and figuratively, on the edge of their seats.

In a similar way to how Duchamp disavowed, through his work, the notion that “it was necessary to produce serious things,” Abloh exercises a method by which entire spheres of design can be disrupted through a tongue-in-cheek, one-liner approach. For a while I believed Abloh to be a past-master in the art of the cadavre exquis, the technique by which words or images are collectively assembled into a hybrid and then scattered to the winds of comprehension. (Incidentally the term cadavre exquis was coined by the Surrealists and their friends—among them Duchamp—after one boozy version of the game had resulted in the word sequence “Le cadavre exquis boira le vin nouveau.”) Abloh’s approach to appropriation continues to ruffle feathers in the fashion and design worlds alike. For some, the “bootlegging” of graphic intellectual property is nothing short of plagiarism. As an artist of and for the social media age, in which context really is everything, Abloh embodies the antithesis of the “@diet_prada” clique — an Instagram account which, by its own description, calls out “ppl knocking each other off lol.” And yet, on reflection, this reading is not altogether accurate. Abloh is a practitioner who demands context in his own practice while, conversely, requiring context in order for himself to be properly understood. The role of any of his single throwaway statements recorded in Incidents, for instance, is made richer when you, the reader, appreciate its relevance in the larger frame of his career. The same, of course, applies to the purveyors of his wares. His self-proclaimed “single body of work” is also a strategy, bounded not by him per se but by the limits of contemporary cultural production.

Given the critical mass of support underpinning Abloh’s every move, it can seem as though at this moment that he has an incapacity to fail. Attentive eyes are keeping themselves peeled for an exhibition that will open at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago (MCA) in 2019. The eponymous Virgil Abloh will show how he has “craft[ed] an all encompassing artistic universe” in furniture design, graphic design, and, significantly, architectural interventions (detailed information was unavailable at the time of writing). A project with the MCA also represents a homecoming of sorts for the Illinois native and, perhaps, a moment in which the breadth of his output to date—albeit presented in a curated, tightly edited, and controlled setting—will be proffered for broader public scrutiny. In a museum context where depth ought to be favored over breadth, Josef Paul Kleihues’s MCA glass ceilings will, one hopes, shed new light on what has only been appreciated to date as a successive sequence of rippling splashes in the proverbial pond.

The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek, building on the thinking of Alain Badiou, describes an “event” not as “a thing that occurs in the world but a change of the very frame by which we perceive the world and engage with it.” While describing Abloh and his output as an epochal event might seem overindulgent it is, for many reasons, appropriate: his game is, at its heart, about proving that a shift in culture is taking place. Fashion, art, music, and spatial interventions (read: architecture) all represent conduits for creative, consumable production. In the end, they amount to the construction of a narrative that speaks louder than the sum of its parts. It should be remembered, however, that the inherent definition of an event is that it is, and perhaps always should be, brief.