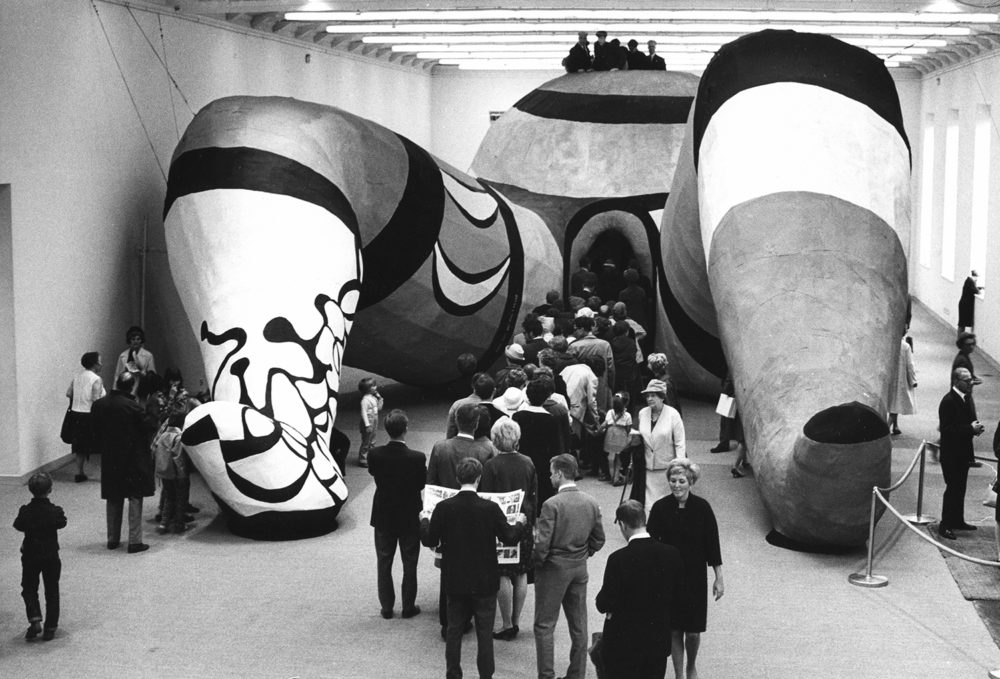

In 1966 Hon – en katedral (She – A Cathedral) opened at Moderna museet in Stockholm. Only a matter of weeks prior, no one involved had any clue as to what would be presented to the public that summer. “The idea was that there would be no preparation,” Pontus Hultén recalled in a 1997 interview by Hans Ulrich Obrist. Hultén, the museum’s director who later became the founding director of the museum of modern art at the Centre Georges Pompidou had, however, convinced the French-American artist Niki de Saint Phalle and the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely to make a trip to Sweden. Triangulating them with the Swedish artist Per Olof Ultvedt, his plan was to have no plan. They would improvise.

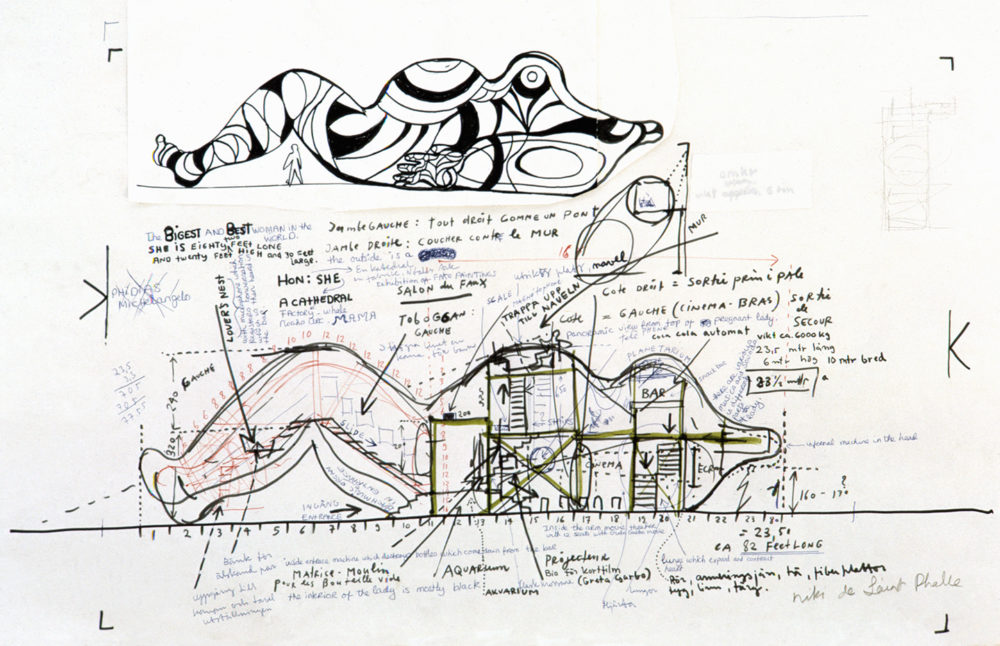

This eccentric collaboration between curator and artists—often ambiguous and, by all accounts, particularly so with Hon—resulted in something extraordinary. Their meeting conceived the figure of a recumbent woman, roughly twenty-three metres wide and six tall. Occupying the museum’s main gallery, a former naval drill hall that today forms part of ArkDes, Hon was a serene yet dominant ‘building’ in a building. Over the course of three summer months, visitors walked around and between its spread legs into an otherworldly, entirely habitable space. A steel skeleton and papier–mâché skin accommodated a milk bar in its right breast and a planetarium, depicting the Milky Way, in its right. There was a cinema, a slide, a gallery of imitation “fake masters” made by Ulf Linde and, protruding from its pregnant belly, a peephole offering the disoriented visitor an apex view over the whole affair.

With a tight grip on the ‘publicness’ of the museum, Hon offered all of the ingredients for a fun weekend excursion. As a sculpture, or a structure, or a piece of public art, it carried as much critique as it received. Through Hon, its creators gave symbolic and substantial life to the idea of the dynamic museum, a territory inexorably entangled with the world it was a part. It was as challenging as it was unaccountable, engineering an inclusive bodily experience for visitors and asserting the local controversies that beleaguered it. As a project, it represents an unexacting attempt at unifying space, art and performance, proving that these overlapping spheres really can make for excellent bedfellows. (Although, perhaps, complex lovers.) Hon was as much a piece of infrastructure as it was a humanoid resplendent; as much an architectural intervention as a collaborative work of art. It dwelled in the museum with sincere intent – but without taking itself too seriously.

The most serious of topics are best framed in a playful way. The lighthearted does not always equate to the frivolous and can provide a point of access to otherwise challenging topics. In 2017, Fondazione Prada presented The Boat Is Leaking. The Captain Lied. The title, referencing Leonard Cohen and Sharon Robinson’s 1988 hit Everybody Knows, only hinted towards the darker themes that the exhibition explored. In an eerily similar framework to Hultén and Hon, and almost precisely five decades later, the German curator Udo Kittelmann chose to embark on an intensive collaboration with the stage and costume designer Anna Viebrock, the sculptor and photographer Thomas Demand, and the writer, philosopher and filmmaker Alexander Kluge. When they began the project some years earlier, none had a clear vision of what the exhibition would ultimately say or contain. Against a backdrop of social fragmentation and cultural disenchantment, the only thing they did know is that they wanted to play with the more shambolic aspects of contemporary life. In an interview published in Mousse shortly after the exhibition opened, Kittelmann described the show as a panorama in excerpts and scenes that describe a world caught up between storms and calm, threats and hopes, standstill and transitions, and truths and falsehoods. “Don’t expect a white cube,” he declared. “It will be the very reverse.”

In the intricate choreography between ideas, people and their work that followed, the group claimed the grand and uneven rooms, corridors and stairways of the foundation’s Venetian palazzo, Ca’ Corner della Regina, as an uninterrupted scenography. Among the film, art and theatre media on display, a visit to the show unfolded the dialogue that had led to their seamless, or consciously fractious, interactions. The arrangement of the works within the rooms, their proximities, and the interplay between built ‘sets’ and the palazzo-proper conveyed a very real sense of unease. Encounters with image, space and sound oscillated between the background and the fore, demanding your attention for a moment before appearing to dissolve entirely. This yawning, see-sawing performance of curatorial control and spatial spontaneity was disarming and disorienting experience.

Hon and The Boat is Leaking… both attest to the notion that exhibitions happen as much to your body as they do to your mind. As regimes of attention, and in different ways, they dealt holistically with the interplay between space (a room), things (an object), and audience (a body). This idea is not mine; I have borrowed it from Kieran Long, my colleague and the current director of ArkDes – Sweden’s national centre for architecture design, the museum now responsible for the space in which Hon resided. In 2013 Long, alongside colleagues at London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, published Curating for the Contemporary: 95 Theses – a series of straightforward statements that questioned the received wisdom of curators, and curatorship, in public institutions. The concluding statement—that “a museum is not a refuge” but “a place to encounter the world in a state of heightened attention”—is an observation that rings ever truer as my understanding of what exhibitions have been, and could be, evolves.

I do argue, however, than the exhibition is performative. At a basic level, it comes to a visitor as much as a visitor comes to it, and this reciprocity constitutes a valuable relationship. Curatorial work should therefore focus on cultivating conversations and then seek to maintain their energy. “Storytellers,” Walt Disney was purported to have said, “restore order with imagination.” At some negligible level, the generation of an exhibition—that commonly represents the distilled, visible tip of an iceberg-sized collection of flotsam and jetsam—is not dissimilar from the work of a Disney-bred Imagineer. Exhibitions instrumentalise ‘things’ from history and the now—ideas, words, objects, individuals and groups, etc.—to tell and trigger stories that ripple outward or resonate forward. At their best they are immersive and inclusive, having whisked ‘things’ in motion out of the ether, or unearthed them from beneath the ground, and then contextualised them into a narrative. An exhibition that is simply an interface, or an attempt to provide a window onto a different world, misses the point. An exhibition should not anaesthetise the complexities that they deal with, but act as a vehicle to understand the world as it exists.

I once heard someone remark that in order to write the briefest of labels for an object in an exhibition requires research on the scale of a book. I then jotted down the following words: TO SPEAK AS IF IN CAPITAL LETTERS. While it might seem hazy or obscure at first glance, it’s a sentence I return to time and again. Capital letters were the written format of telegram transmissions, for example, in which messages sped around the world often in fewer than fifteen words. Today we might use capital letters when we’re filling out a form. Writers might use them emotively in a script to emphasise a voice. Sometimes they can indicate a raised voice and, when taken out of context, might appear wholly rude. But capitals equal clarity. Like the marks of an editor’s red pen across a manuscript they are self-edited and concise, unambiguous and clear, and still embody all the gradation in and complexity of language.

There is not a great distance between an emphatic approach and a didactic one, of course; the latter runs the unproductive risk of alienation. With that in mind, an exhibition is at its best when quivering between emphatic and nuanced communication. (In different ways, Hon and The Boat is Leaking… trod this tightrope deftly.) At a time largely defined by a tender self-obsession, in which it is increasingly difficult to avoid feelings over things or facts, the exhibition has a role to play in bridging and clarifying, prompting and responding and, ultimately, inspiring. Any idea that they can change the world, however, is an illusion. They should be capsules, not monuments.