“St. Mark’s is flooded!” A day tripper to Venice is astonished. “This place really is sinking,” her friend exclaims. They, like so many I’ve overheard on the vaporetti, are convinced that the Venetian islands exist on a precipice between timeless fragility and nothing short of imminent submersion. With catastrophe a seemingly perpetual possibility, a weekend in Venice might better be described as a thrill seeker’s adventure trip than a serene city-break. If it were true, that is.

Venice is not sinking – it’s flooding. Since time immemorial the city has been periodically submerged as a result of tidal patterns. Residents are dutifully accustomed to its wintertime rhythm and, less frequently, during summer. While acqua alta (high water) is little more than a fascination for visitors, it is an accepted inconvenience for those who live with it: ground floor doors must be sealed with barriers, boots and dungarees have to be fished out of the closet and, if the water is particularly high, boats are unable to pass beneath the lower of the city’s bridges until the water subsides. To keep feet dry, walkways are erected throughout the city and people continue normalcy as best they can. (I once joined friends for dinner during a freak summer sirocco wind-induced acqua alta on Fondamenta Ormesini – we sat outside, submerged, and ate calamari.)

Venice has always had a uniquely intimate connection to the lagoon it is a part of. Its first settlers were refugees, fleeing to the marshlands in which the city now stands in order to escape Germanic tribes and violent Huns. The first structures they erected on the rivoalto—a small constellation of islands where the Rialto and its bridge now stand—were built atop wooden piles – a unique process of petrifying sunken columns in the silt of the swamp, still in use today. Even as the city expanded its empire into La Serenissima—the serene Venetian Republic, one of the most powerful thalassocracies that the world has ever seen—it was habitually reminded of its delicate, defensive, and highly lucrative relationship with the lagoon and seas beyond. The ancient and mystical annual Marriage to the Sea (Fig 2), established around AD 1000, saw the Doge hurl a consecrated ring into the murky waters before declaring the city and the sea to be indissolubly one. This liturgy provided a civic demonstration of the fact that prosperity could only perpetuate if the forces of nature would allow.

A version of this nuptial ceremony continues to this day. Over recent centuries, and especially since the 1970s, Venice’s economy has exchanged the import and export of goods for the import and export of tourists. Any naval presence has been superseded by unsettlingly large cruise liners, while swatches of San Marco, Cannaregio, and the Dorsoduro are now occupied by an astonishing number of hotels and holiday houses. Many Venetians have either been driven out of the city by lack of work or have left of their own accord. Contessa Jane da Mosto, an environmental scientist who has lived in the city since 1995, is one who has, against the odds which have forced others onto terra firma, actively made the lagoon her home. She and her husband, Francesco da Mosto, have together raised four children in the city against the threat of a domestic exodus.

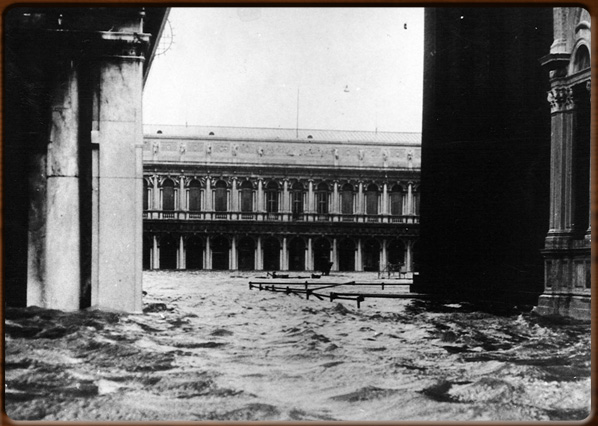

In discussion about the history of Venice and the lagoon which it is a part of, Da Mosto points to one event that altered attitudes in and of the city: the devastating flood of November 4th, 1966. Reaching a wholly unprecedented 194 centimetres, heavy rain, a severe sirocco wind, crumbling infrastructure, and an entirely unready population isolated the city for 24 hours without repent. The freak acqua alta revealed for the first time in a century the extent to which the built fabric of Venice had deteriorated. In the words of British art historian John Pope-Hennessy, it exposed the “havoc wrought by generations of neglect.”

“Venice lives thanks to big disasters such as this,” Da Mosto argues. “They have caused [the city] to fundamentally change direction.” At the point at which the 1966 flood occurred more and more of the lagoon had been absorbed by the expansion of the nearby industrial zone in Marghera. “The national and international attention that followed this event changed the emphasis to safeguarding the heritage of the city.” As part of what became known as the International Safeguarding Campaign, investment flowed into Venice from around the world and its decaying skeleton gradually began to breathe new life.

In November last year, 50 years on from the 1966 flood, We Are Here Venice—an organisation founded by Da Mosto to raise awareness of the issues that the city now faces—inscribed a blue line around the shop windows and doorways lining Piazza San Marco. L’Acqua e la Piazza (“The Water and the Square”) sought to graphically indicate just how high the water rose that day. “A strong storm surge meant that the excess water didn’t leave the lagoon when the tide turned and, combined with a sort of oscillation in the Upper Adriatic—just like when you’re in the bath and the water rocks back and forth—extra water was pushed into the lagoon.” As the water expelled and ‘hit’ the opposite coastline of the Adriatic, it simply returned and washed back into the Venetian lagoon. This back and forth motion, Da Mosto explains, can sometimes occur for days on end until the water eventually dissipates through the Adriatic and into the Mediterranean Sea.

Following the disaster, which also caused considerable damage to other Italian cities on or near bodies of water, repairs and restorations were carried out to ageing monuments as matter of urgency. In the 1980s, MOSE (named as an homage to Moses, the Biblical figure who is recorded to have parted the Red Sea) was commissioned: four vast retractable gates at the inlets of the Lido, Malamocco, and Chioggia which, when finally operational later this year, will be able to seal the entire lagoon from high tides in 15 minutes flat. The project, akin to the Thames Barrier in London or the Maeslant Barrier in Holland, has been mired in a corruption scandal (€5,493,000,000 has been spent on the project to date) and by no means offers an even semi-temporary solution. “Even when the mobile barriers start operating,” Da Mosto iterates, “Piazza San Marco will still be flooded many times a year. […] It’s absurd to think that mobile barriers alone can save Venice,” she argues. “They are just one of the many measures that are needed in the lagoon.”

“The last 30 years,” she explains, “have been heavily conditioned by strong lobbies that permeated every nook and corner of the cultural, scientific, and economic life of the city. They have all been associated with a huge flow of investment through the 1973 Special Law for Venice [which aims to “guarantee the protection of the landscape, historical, archaeological and artistic heritage of the city of Venice and its lagoon by ensuring its socio-economic livelihood”] that was directed at building the mobile barriers. But, as the scandal has revealed, over a billion Euros cannot be traced. To add insult to negligence, the money focused on the actual works has been shown to have been spent at inflated prices. So not only did a huge amount of money disappear, but they have simply spent more than they should have.”

For a city which has always relied on an economy driven by foreign trade, plans with the ambition of the MOSE project are nothing new. Venice has always made courageous efforts to maintain accessibility between the sea and the city to safeguard its interests. “When the lagoon first started to silt and navigation became difficult, the city diverted whole rivers further south or further north of the lagoon so that less sediment came in and they could keep the channels deep for the galleons,” Da Mosto states. “Subsequently, during Austrian occupation at the end of the 19th Century, the entire coastline of the barrier islands to Venice were reinforced, and proper inlets were built to ensure that access to the lagoon was deep and wide.” Unfortunately, as a consequence of that and many other similarly short-sighted moves, Venice is at risk of no longer being part of a lagoon system at all; as channels are dredged ever deeper to accommodate the likes of MS Queen Victoria (a 90,049 gross ton pleasure-cruiser operated by Cunard) in port, it is being transformed into less of a lagoon and more into a bay of the sea – and that, according to Da Mosto, “has very important implications for the integrity of the city as well as its biodiversity and ecological functions.”

There can be no doubt that Venice lives thanks to the regular exchange between the lagoon and the sea and, while there is still an inherent resilience in the system, much has been neglected over the preceding decades. “We’re beyond the times when some ministry for infrastructure and public works can just come and do what they want to do, or what business interests make them do,” Da Mosto argues. “The whole city needs to wake up.”