Tomas Koolhaas, a director critical of films about architecture or architects “made up of talking-head interviews interspersed [by] static, lifeless shots of empty structures,” proposed in 2015 that REM—a film about his father, the architect Rem Koolhaas—would be the first documentary in its genre to comprehensively explore “human conditions” in and around a collection of projects designed by his practice, the Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA). Based on this vision, and coupled with the inevitable international interest attached to projects bearing the name of the firm or it’s founder, over a hundred crowd-funders pledged just over $30,000 to part-finance its production. REM, which has been four years in production, premiered this Autumn at the 73rd Venice Film Festival.

Carried forward by Murray Hidary’s unbroken orchestral score, the energy of the picture’s opening sequence is baffling, if not beautiful. It’s dusk in Porto: a skater (slash-dancer-slash-parkour aficionado) leaps into the Casa da Música (2005)—a great balancing boulder of a building—as his board rolls off-screen and a cello appears to bellow from deep within its core. The place is empty but for the dancer and, as he twists, slides and reverberates around ramps and rooms, the score builds. He pauses for a moment in a tiled space as the music breathes for him, but his destination is in fact beyond: he scales a staircase and stands beneath a glazed ceiling, which duly opens to the sky. As the filtered light gradually becomes more lucid, “REM” fills the frame.

While incongruous in the wider context of the film, this choreographed sequence does embody a more implicit message, writ large throughout the picture. The momentum of this title sequence scene soon gives way to a more sedated repertoire of pacing (cities, the countryside, desert dunes), sitting (offices, planes, cabs, boats), swimming and, to a lesser degree, standing (conversation, presentation) – but forward motion, in all its variety, is established as a baseline motif. The metaphor, if there is one to uncover, extends further: while the vitality of youth has subsided into senescence, an unmistakable sense of urgency—so recognisable in the architect’s writing and words—endures.

REM’s point of departure—“the beginning; […] the foundation of everything else,” as Koolhaas narrates—is New York City. Following a stint at London’s Architectural Association (an unfolding hotbed for architectural experimentation under the direction of Alvin Boyarsky, at the time) Koolhaas relocated in 1972 to begin work on Delirious New York, a retroactive manifesto for a city apparently lost in a tailspin of urban decay and economic recession, and tainted by an all-pervasive bleakness. But it’s “grunginess” also made it ripe for reading afresh – “it’s always right before a storm that the air is filled with dangerous possibilities,” the Transgressive film director John Waters once recalled. In fact, the city had many of the qualities of Rotterdam, the tabula rasa Dutch port in which Koolhaas would eventually base his practice: once second-rate, still emergent, and primed for radical intervention.

New York is one of a diegetic sequence of markers which, when read together, present a decisive and very deliberately composed narrative. These chapters, however, are also layered with ambiguities – often ramified by intensive editing and a byproduct, perhaps, of the sheer scope and ambition of the project. It is clear that REM has been formidably challenging behind the lens, but Tomas has nevertheless created a powerful cinematic experience, the calibre of which is comparatively unparalleled in the world of architectural film. Those audiences searching for superficial insight will undoubtedly be left unsatisfied, and rightly so: Koolhaas flies Transavia, a budget-level subsidiary of KLM. He almost exclusively wears Prada. He doesn’t use an iPhone. And that—thank goodness—is your lot.

But a human-interest story, similar to that of Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect (2003)—the narrative of a son’s journey to connect with his deceased father, the architect Louis Kahn—was never going to be the deal. While REM is also billed as a documentary, it is positioned as both sincere and significant in order to neatly sculpt the story of its eponymous protagonist into a tight, rigorously edited narrative; the persona which emerges is at once charismatic, enigmatic, and characteristically reticent.

A certain degree of reticence is to be expected. For a scriptwriter-turned-journalist, and a writer-turned-architect (if those disciplines can indeed by considered separate), Koolhaas has more experience than most in recognising the power and potential pitfalls of too much, or too little, publicity. The Dutch translation of “editor” is redacteur – a word that, once anglicised, references the process of redaction or, in its most extreme definition, that of censorship. REM is heavily edited, sharply focussing in on a collection of grand narratives—building in the Middle East, for example, or the media, or the countryside—while other more obvious themes, such as the operation of OMA, or the ways in which he collaborates with others (both Marina Abramovic and Hans-Ulrich Obrist make enigmatic appearances), dissolve into a bokeh blur. If you accept that the story being told is being revealing in a carefully constructed way, frustrations are few; if not, scenes can feel curtailed and, at worst, hollow.

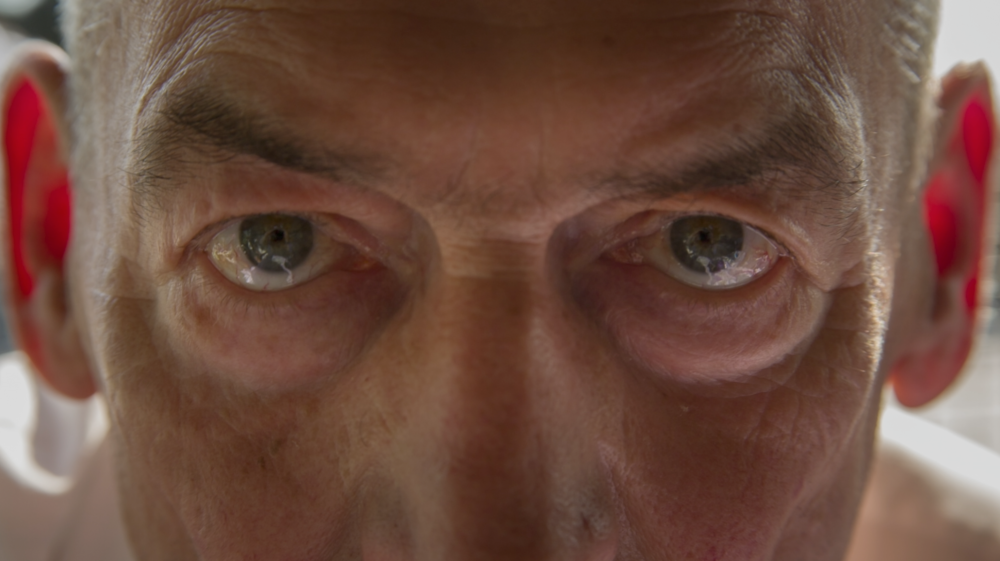

Two cinematic techniques construct the film’s authenticity: the authority of Koolhaas himself, which spans almost the entire feature through a series of monologues, and the fact that Tomas—his son—is behind the camera. Positioned one step behind the architect, the audience becomes particularly au fait with the back of Koolhaas’ head and shoulders. At moments in which REM’s leading character does directly address the lens—through incidental glances, on the most part—the gulf between the audience and Koolhaas feels even larger. He’s not looking at us, we realise; he’s catching sight of Tomas. If the audience is unconsciously triangulated in a relationship between father and son under the auspice of a biopic, REM is in a unique position to assemble the most intimate portrait of the architect to date, and it’s a situation exploited to maximum effect.

Koolhaas swims every day. He used to run, but he now swims regardless of where he is in the world. When in Rotterdam, for example, you’re likely to find him swimming at the David Lloyd on the corner of Schiekade and Heer Bokelweg. While REM records him plunging into rocky coves and bright blue ocean, we learn that the reasoning behind the ritual is the same: exercise, for Koolhaas, is a sociological undertaking. “Nothing,” he believes, “is more revealing than seeing how people move in or near the water.”

The portfolio of projects which Koolhaas (and, by extension, OMA) has to his name—books, buildings (realised and, perhaps more importantly, those not), exhibitions, and university studios—have often been the result of actively swimming against disciplinary occupations of the moment. It’s a fact which he himself readily accepts: “If you would caricature my life, or my career, you could say that by saying the opposite of everyone else many times I turned out to be right.” And in the beginning, back in the 1970s, this was possible. Even in the early noughties, when AMO (the research arm of his practice) was commissioned by the European Union develop The Image of Europe, Koolhaas was well positioned to be able to operate as a cultural intellectual at both the peripheries and the heart of the architectural sphere.

As his public persona has ballooned into that of celebrity, the popular perception of his work and ideas have become more closely affiliated with his role as an architect. This is, of course, a double-edged sword; on the one hand, as he narrates: “I could never have done what I did without being relatively known. It extends your range.” On the other, it runs the risk of collapsing into a self-defeating effort: “Every time [you talk to the media] you wonder if it makes any sense. The tendency,” he believes, “is to create a single caricature of how difficult you are to get, how intermittent your attention is, how hurried you are – even if you talk to them for two hours.”

REM, itself partially an exercise in public relations, is refreshingly uninhibited about the paradoxical relationship between exposure and the upshots of publicity—an evermore voracious appetite for ideas, opinions, and soundbites. Fundamentals and Absorbing Modernity 1914-2014—the two exhibitions Koolhaas directed for the 14th Venice Architecture Biennale – were immense and demanding undertakings. In one scene, in which the architect is encircled by a ring of journalists each brandishing microphones, cameras, lights and notepads, the film attempts to zero in on this phenomenon. Following a press conference, Hidary’s score breaks completely (for the one and only time) as a television reporter challenges Koolhaas to describe what visitors to the Biennale should expect to see. Looking to the floor and wiping his brow, he replies: “Sorry, I can’t answer that question. Just read the text. […] I’m not interested in take-my-hand questions.” Frustration fades into feigned-acceptance.

If the Biennale marked a break in Koolhaas’ thinking—a condensation of all that had come before—the subject of the film’s final chapter is markedly more propositional: “The city is no longer,” he declares. “We can leave the theatre now.” For over twenty years Koolhaas has visited the same Swiss alpine village in the Engadin valley – a hiker’s idyll caught between St. Moritz and the Italian border. Here he has observed patterns of change—from demographic shifts and the effects of issues of scale, to the emulsification of architectural styles—all at one time imperceptible and now increasingly evident. The countryside has revealed itself as being just as contradictory as the city.

While cities currently occupy only two percent of the surface of the Earth, the architectural profession feels to be, at times, ninety-eight percent preoccupied by them. Koolhaas has been investigating these antinomies at full pace for four years now; in 2012 his practice presented an exhibition at Amsterdam’s Stedelijk in which they put forward a manifesto on the topic informed in part by Henry David Thoreau’s Walden – a memoir often referred to as an advocate of self-reliance and highlighting the perceived “illusion of progress.” That same year Koolhaas described the “hinterland” as “an arena for genetic experimentation, industrialised nostalgia, new patterns of seasonal migration, digital informers, flex-farming, and species homogenisation.”

Although a century-long focus on the city has blinded many practitioners to the incredible changes happening elsewhere, we must accept that both are intimately connected. Many of the transformations taking place in the countryside are being enacted to preserve the city. For Koolhaas, this thought is prophetically exciting: perhaps one will formalise more rigorously—that is, become more “Cartesian”—in order to sustain the other and support increasing frivolity and freedom in the way urban structures are designed and built. In some parts of the world rapid automation of the countryside is already taking place, and a digitised, highly artificial post-human architecture is starting to develop under our very (everted) eyes. The perseverant search for terra incognita, therefore, continues – and REM, in this context, is little more than a pregnant pause.

“Before everything,” Koolhaas remarks, “I was, and maybe still am, a journalist.” REM has provided a unique opportunity for both Tomas and his father to carefully redact, reformulate and represent the narrative of a career which has been discussed, criticised, and lauded more than any other living architect. Although four decades have been compacted into four years of filming, and four years of filming have been compressed into seventy-five minutes, any form of nostalgia is virtually non-existent. Although rarely poignant it is highly personal and, for me at least, is all the richer for it. Objectivity is often overrated.

Uncharted territory is what has always attracted me the most. Of course I’m aware that this cannot be an endless sequence anymore but, for the time being, I’m motivated to continue reporting. —Rem Koolhaas