Sigurd Lewerentz (1885–1975) remains, for many, an enigma. The late Swedish architect elected silence not as a tactic per se, but as a state of being. He did not write, nor did he speak (much). He built, diligently and poetically, resisting the urge—if it ever existed—to define the ethics or aesthetic framework which bound together his body of work. To echo the words of Colin St. John Wilson, paraphrasing E.M. Forster’s impression of the Greek poet Constantine Cavafy, it was “as if he stood at a slight angle to the world.”

Silent, however, does not mean that Lewerentz had nothing to say. In their text The Silent Architects in the 1989 anthology Sigurd Lewerentz, 1885–1975: The Dilemma of Classicism, British architects Alison and Peter Smithson—among the few of Lewerentz’s contemporaries abroad who, perhaps unsurprisingly, recognized the power of both his architecture and his oblique persona—averred that silent architects, who are defined by what they do rather than what they say, are “by the complexity of invention, unaware of doing.” To the Smithsons’ minds, it was what archi-tects of Lewerentz’s ilk are unable to talk about that shifts the tide of architecture. And yet, in spite of his fundamental role in the development of the discipline in Sweden, he remains comparatively obscure. Compared to the more direct charisma of his early collaborator Gunnar Asplund, for instance, Lewerentz’s “silence” has turned him into a figure of veiled legend. The ramifications of the resurgent interest in his practice are now posing a challenge: in the absence of one-click primary context, anybody is able to project anything they choose onto his identity, his intentions, and his ideas. He is fast becoming the most interpreted architect of the Swedish canon, and the myth, therefore, is mushrooming.

Lewerentz is fabled first and foremost for his sacred spaces: cemeteries, landscapes, chapels, and tombs, which, in the case of the Woodland Cemetery in Stockholm (1915–40) or the Eastern Cemetery in Malmö (1916–73), can be experienced as single compound symphonies. His is an architecture of dignity: a balance between intimacy, intricacy, and grand gesture, of ritual and symbolic form, and the conviction of close-looking. Aside from ware-houses and factories, storefronts and advertisements, civic spaces, and door handles (under the auspices of IDESTA, a window, door, and detail company he established in 1929), it is his domestic projects—villas, primarily—that offer a lens through which to comprehend his way of seeing.

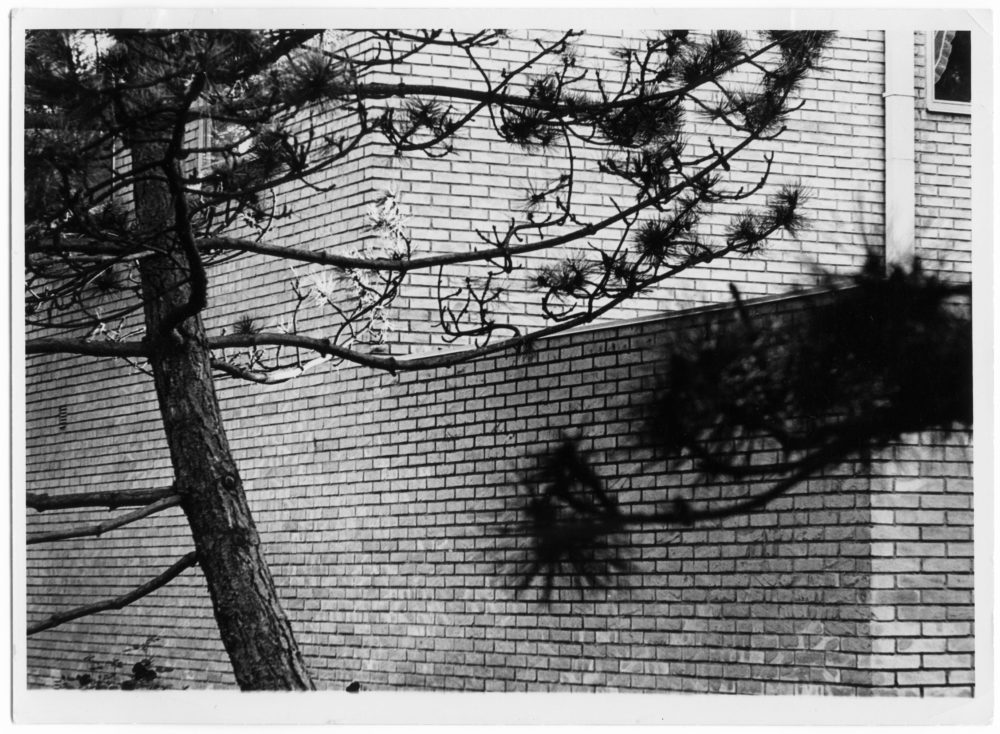

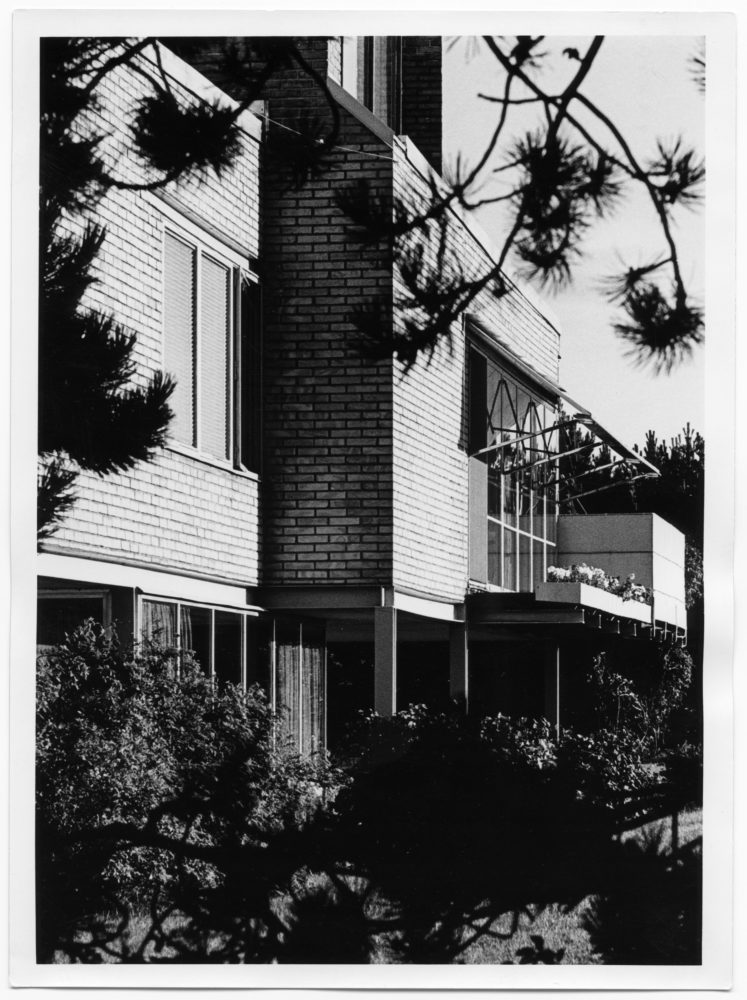

Shortly after, and perhaps as a result of, the pivotal Stockholm Exhibition of 1930, in which the Functionalist movement, steered in part by Lewerentz and Asplund, was ushered to the fore, the steel magnate Knut Edstrand commissioned a summer home. Located in Falsterbo, a small sandy head-land on the most southwesterly tip of Skåne, and facing Copenhagen across the Öresund Strait, the Villa Edstrand (1933–37) provided an opportunity for Lewerentz to experiment with the design of the home and with artisanal craft. In the words of his biographer Janne Ahlin, Lewerentz was, by this point in his career, ever less reliant on exterior belief systems; more assured in his own, internal ideals—whatever they might have been—he designed a boxy, low-slung structure built from concrete, steel, wood, glass, and yellow brick.

A distinctly Functionalist design, the Villa Estrand, like a slice of schist, perches on the sunken peninsula in a spatial sleight of hand. Angled toward the blue marine horizon, it is crested by a secluded terrace, much like the upper decks of an ocean liner, which was deliberately designed to resemble the bridge of a ship. Lewerentz seized the opportunity to innovate and experiment on every scale. The large expanses of window performed as real-time testing grounds for new, exploratory detailing. Steel lintels and their joints were left bare and exposed. Electrical wiring was allowed to trail lackadaisically along the interior walls (a move similar to one of his final, much admired projects, the 1969 flower kiosk at the edge of Malmö’s Eastern Cemetery). A staircase climbing to the villa’s highest terrace was suspended with remarkable minimalism, accompanied by a simple nautical rope as a handrail.

Executed with intense precision, the Villa Edstrand was, in essence, Lewerentz’s large-scale prototype for a new way of living. Inspired to a great extent by Le Corbusier’s villas of the preceding decade and the ideals of the International Style, Lewerentz proved himself able to expropriate and then deform a vision of a coming world into something that would now, perhaps, be described as singularly svensk. He was a product of the moment he occupied and, in the same breath, stood among its chief form-givers. This coming world, largely shaped by utilitarian Functionalist principles and humanist values, was to be defined by the dialectics of transparency and seclusion, playfulness and sobriety, and the blend-ing of landscape—woodland, water, the wilderness beyond—with the unadorned, livable interior. The Villa Edstrand, today broadly unknown and, at worst, ignored, stands as a model for an ideal of domestic life whose narrative—in Sweden, at least—remains strong, but whose materialization never took root.