In the nascent days of the European Age of Enlightenment, Lisbon stood as one of the great European capitals. The 18th Century saw Portugal almost entirely fuelled by a colonial gold-rush: extraction in the Americas had steadily winched the country out of a deep financial trench, fortifying its commercial prosperity and an appetite for progress. The absolute monarchy was in its ascendency and a gilded, if not gradual, restoration of national pride was resurrecting the nation’s intellectual prowess until, out of the distant blue, disaster struck on an unimaginable scale.

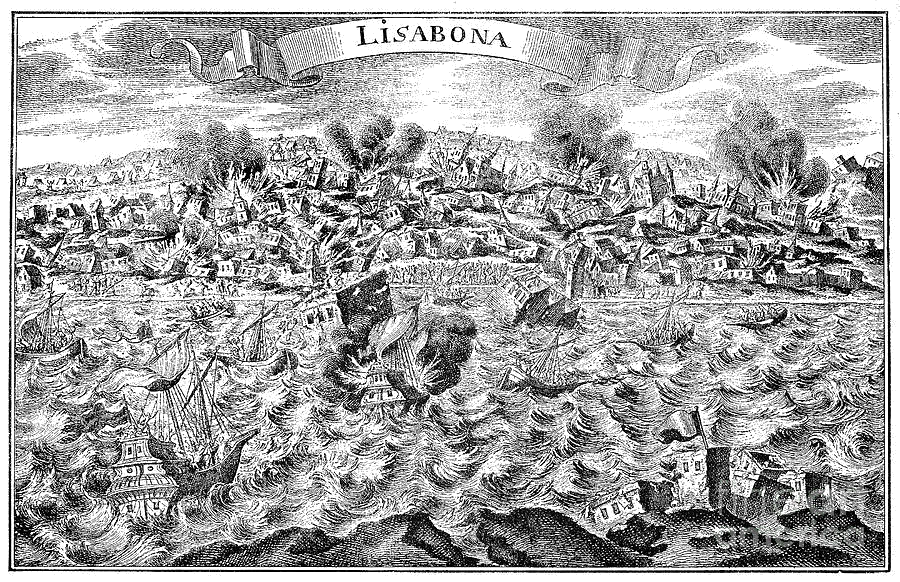

In 1755, on All Saints’ Day at around 9.30am, an earthquake echoed violently off the Iberian Atlantic coast. In the minutes following, tremors rippled toward the mainland; the streets of Lisbon were torn open by giant fissures and, in a desperate search for safety, people ran to the open space of the docks. To their complete incredulity, the river before them—the Tagus—had been entirely emptied of water and now stood littered with shipwrecks and long-lost cargo. In the subsequent moments of confusion the survivors started to assess the damage: large swathes of the city had been demolished and what appeared to be an incalculable number of people had been crushed, trapped or injured. But before the awful horror of the situation could truly set in the first of three tsunamis crashed headlong into the coast and surged down the estuary. Those structures which had not collapsed during the earthquake were now razed and washed away; those survivors who had been stood on the water’s edge suffered a similar, terrifying fate. The higher areas of the city (which had been relatively unaffected thus far) soon found themselves engulfed by a fire that would rage for days to come – earlier that morning, thousands of candles had been lit around the city to mark the religious festival. Within the course of a single November morning the flourishing capital of a transatlantic Empire had been unequivocally brought to its knees.

In November 2014, Rogue—the seventh instalment of the largely fictional Assassin’s Creed saga—presented hauntingly realistic game-play set during this catastrophe, the simple aim being to “Keep Moving Forward” and “Escape Lisbon.” You (as Cormac, the game’s tricksy protagonist) dive and jump through winding streets, dodging collapsing buildings and mercilessly rushing past people in the eye of a living nightmare. Glossing over the historical inaccuracies this is just about as visceral an experience that one can have of that sequence of unfortunate events. Records from the time also present a stark picture: in the wake of the catastrophe the damage, both material and in terms of the national consciousness, was deeply felt1 – after all, tens of thousands of people had died for no apparent reason. The disbelief that subsequently spread through European intellectual circles focused primarily on the devastation of Lisbon itself; philosophers and theorists felt compelled to ask why such indiscriminate horror had been dealt to the Portuguese capital. While Immanuel Kant sought to lay out its scientific causes,2 in December of 1755—just prior to the publication of Candide—Voltaire’s Poème sur le désastre de Lisbonne (Poem on the Lisbon Disaster) attempted to come to philosophical grips with the disaster:

Lisbonne, qui n’est plus, eut-elle plus de vices

Que Londres, que Paris, plongés dans les délices:

Lisbonne est abîmée, et l’on danse a Paris.Did fallen Lisbon deeper drink of vice

Than London, Paris, or sunlit Madrid?

In these men dance; at Lisbon yawns the abyss.

The 1755 Lisbon earthquake has served as a touchstone for a number of thinkers since. Zygmunt Bauman (1925-2017)—the late sociologist, ethicist and political philosopher—attached particular significance to the event: “a wave of fear” emanated from it, he argued, because it just seemed too contrary to reason.3 Until that particular tragedy Europeans had held unshakable faith in a traditional belief-system (which was bolstered by the religious teachings of the time): namely, if one acted virtuously one could expect reward in both life and in death, even if that reward was simply being spared from life’s unpredictable terrors, while those who sinned would be duly punished. The fear of living in a world of inexplicable insecurity that stemmed from the Lisbon disaster mushroomed across political hearths and centres of thought until a state of uncertainty became the predominant state of being. This newfound reality, Bauman believed, has not to this day shown any signs of abatement. For him, Lisbon was the moment which triggered the European Enlightenment, igniting the process of secularisation [read: Modernity]. “The idea was to tame nature,” he maintained – to “make it subject to intentional action, hoping that if everything is planned and designed the age of catastrophe will come to an end.”4

The age of catastrophe shows little sign of coming to an end. The increasing volatility of modern life was the subject, either explicitly or indirectly, of much of Bauman’s writing – the notion that our national (and therefore international) and personal safety, our individual position in society, relationships with our friends and our loved ones (now only “until further notice” rather than “till death do us part”) are all more fragile than we might at first concede. The framework of our lives is comparable, if you will, to the structure of an eggshell: if we apply enough downward pressure then they might just hold out – but if they take an unexpected blow from the side they will almost certainly crack and, at worst, crumble before our very eyes. What are we then left with? Little more than a viscid mess from which we must make an omelette as best we can. At present, Bauman maintained, humanity is wading through an era of unprecedented insecurity—an interregnum, or sede vacante, to go all-out-Latin—in which the political (national governments), social (consumer-led) and economic (neoliberal) mechanisms that have been deployed thus far no longer function properly in a world of globalised power patterns. At the same time, new ways of structuring society to replace these ailing and outdated models have not yet been invented – “the old is not yet dead and the new is not yet born,” as the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci pertinently put it. Bauman, with a little more buoyancy of tone, argued that “at best” new frameworks are “on the drawing board.” While some labelled him a pessimist true to the lineage of Voltaire he was, in fact, nothing of the sort. A short-term sceptic, perhaps, but Bauman was also a ‘long-term optimist’ arguing, on more than one occasion, that if (and when) humanity can overcome “the long road ahead” and unite, it will thrive.5

In order to appreciate Bauman’s thinking, it’s important to understand the path which eventually led him to the Sociology Chair of Leeds University, in England. As a Polish Jew born in Poznań fourteen years before the 1939 Nazi invasion of Poland, his early life oscillated between extremes: on the one hand, widespread hatred—anti-Semitism, in particular—and, on the other, radical political ideologies. Once war broke out and his family fled to the USSR he was forced to relinquish his academic studies. He eventually joined the Polish Army in Exile (the First Polish Army) but what actually occurred during his military service is unclear and, at times, hotly debated. While it’s evident that he superficially bought into Marxist ideals it’s unclear as to what extent; as a skilled wordsmith and thinker he was drafted as a manifesto-writer who surely worked as a propagandist, too. Following the armistice he returned to Poland and remained in military service, rising to the rank of Major only to be dishonourably discharged in 1953 (the reasoning behind this move, it seems, was due to his father’s vocal wish to emigrate to Israel). In spite of this, Bauman swiftly consolidated an academic position in sociology at Warsaw University, becoming a Professor in 1964. In 1968, amid the events of that year that saw Mieczysław Moczar mount a fervent homegrown anti-intellectual and anti-Semitic campaign, Bauman and his family were forced to leave their country for good. Following four decades defined by totalitarian regimes, he eventually settled in the United Kingdom.

Although Bauman’s early veneration for Communist ideology waned, the work of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels remained influential. The underpinning concept behind his sociology—the concept of Liquid Modernity (Polity, 2000)—has its roots in the 1848 Manifesto of the Communist Party; the terminology itself (‘liquid’ as opposed to ‘solid’) referencing to the Marxist dictum of “all that is solid melts into air.”6 But rather than project a utopia, Bauman’s theories (often mistakenly described as dystopian) offer explanations for contemporary existence. Modernity, Bauman argued, has been and gone – and Postmodernity too, for that matter. Society’s solidity has been liquified through processes of deregulation, liberalisation, “unbridling the financial, real estate and labour markets” and the easing of the tax burden; in other words, it has become like quicksand beneath our feet.7 Throughout the course of the 20th Century the melting pot of Modernity has been silently—if not drastically—recast and refashioned to produce a new, globalised form of power which, in its wake, has also heralded “the end of the era of mutual engagement.” To put it in another way, there’s no longer dialogue between the supervisors and the supervised, capital and labour, leaders and their followers or, indeed, armies at war.8

Modernity in its liquid form hinges on continual process of “liquefaction, melting and smelting,” as Bauman neatly described it.9 Whereas it once possible to bet on job security, for example, Millennials and those of Generation-Z lack a destination; for most, the expectation of a golf club membership through which to eek out one’s retirement in checkered bliss is no longer a viable aspiration. While a conventional labour-free retirement appears to have all but dissolved, speed and progress sustains the course of society just as it has since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. The metaphor Bauman often called upon to describe this condition was that of skating on thin ice – as long as we keep on moving, we’re unlikely to collapse into the icy waters below… but the threat is omnipresent all the same. One could argue that the metaphorical ice is melting, too: the most concerning consequence of being without a shared goal (or a strong set of institutions to guide us) is our inclination to react to problems as they emerge by “groping in the dark.”10 To take, perhaps, an obvious example: faced by the perceived threat of large numbers of immigrants citizens of the United Kingdom voted in 2016 to abandon the European Project without having any concrete understanding of how things will actually change. How will the country trade? What will be the fate of resident citizens of the European Union? The list of concerns can go on but the doubt remains the same: the blind are leading the blind.

Among the nigh-on seventy books that Bauman published in the second half of his life, a large proportion were dedicated to the phenomenon of 21st Century mass-migration. As a theme, it ties together a number of components which underpin the theses of Liquid Modernity—emancipation and liberty, individuality, time and space, labour, community—and together offer a tangible reflection of our present, global circumstances. Bauman was, of course, an emigrant and an immigrant on more than one occasion and Strangers at Our Door (Polity, 2016) deftly dissects the constellation of issues which concern contemporary population movement. He saw cities as a key battleground because they inevitably “generate the contradictory impulses of ‘mixophilia’ (attraction to variegated, heteronymous surroundings auguring unknown and unexplored experiences) and ‘mixophobia’ (fear of the unmanageable volume of the unknown, unnamable, off-putting and uncontrollable).” This is most apparent to those who are neither fortunate nor privileged and who therefore cannot “insulate themselves from the discomforting, perplexing and, time and again, terrifying turmoil and brouhaha of crowded city streets.”11 Paris and its banlieue offer an extreme European example of urban segregation and class-division. In France, the right-wing populist Front National collects votes from the lowest tiers of society – those who are “disinherited, discriminated against, impoverished, fearing exclusion” and who are therefore searching for a scapegoat.12

Our permanent ambivalence to city-life can also be read as a microcosm of society at large. In Liquid Times (Polity, 2007) Bauman argued that whereas the notion of an ‘open society’ once stood for “the self-determination of a free society cherishing its openness,” it now brings to most minds “the terrifying experience of a heteronomous, hapless and vulnerable population.” This population, “overwhelmed by forces it neither controls nor fully understands” and “horrified by its own undefendability” is therefore obsessed by the permeability of its borders and the security of its individual citizens.13 These thoughts, published a decade ago, foresaw our present reality. We surrendered a great deal of security in order to be measurably more free than our great-grandparents but, as the tables turn toward greater security, we must now accept surveillance, controlled access and restricted movement—often self imposed in a self-reinforcing cycle of anxiety—as our sacrifice.

Ultimately, Bauman’s observations stem from the conjoined issues of integration and segregation. In times gone by it was possible to integrate a people by employing the tool of separation – to bring people together all one had to do was point to a joint enemy and instil a sense of fear. In the feuding city-states of the Italian peninsula in the 16th Century, for example, it was common practice for sworn enemies to unite against ‘the French’ or ‘the Spanish’. They represented the ‘other’, a threat worth pulling together and fighting against so that the normal arrangement of localised fisticuffs could resume. Now, for the very first time, humanity has been put in a situation in which we “have to commit to the next step on the road to integration without separation.” Whereas “separation was always the instrument of the integrating effort,” Bauman argued, the new necessity is to develop a ‘cosmopolitan consciousness’ that includes everyone.14 During a moment of intense, largely uninhibited and truly universal access to information, it’s much more difficult for a government or party seeking office to point to a single ‘other’ – as much as they might try from The Netherlands (Geert Wilders) to the United States (President Trump).

In Retrotopia (Polity, 2017) Bauman offered a stark prognosis of what we might expect in decades to come: “So far, there are few if any signs that the challenge [of integration and separation] is likely to be met head-on and soon.”15 The so-called ‘refugee crisis’, which started to gain real media saturation 2015, will probably prove to be the first of many. “The present task of lifting human integration to the level of all humanity,” Bauman argued, “is likely to prove unprecedentedly arduous, onerous and troublesome to see through and complete.”16 Commenting on the European situation specifically, the Slovenian philosopher and cultural critic Slavoj Žižek noted that the core task at hand is no less than “radical economic change that abolishes the conditions that creates refugees.” When he was young, he noted, “such an organised attempt to regulate the commons was called Communism”17 – a comment which, at the very least, offers pause for thought.